If what they say is true, and you really shouldn’t meet your idols, perhaps it’s best to reimagine them. It’s a road many filmmakers have traveled while exploring the legacies of their chosen idols, liberally twisting the dials until a living, breathing person more neatly matches the image in their head. The arrangement has worked out just fine for audiences, turning the biopic genre into one of Hollywood’s most reliable revenue streams, but Richard Linklater has never been one to let ticket sales show him the way. A formal iconoclast powered by relentless curiosity, the director has a way of taking tried-and-true formats and bending them to his will, making his obsession with the French New Wave movement of the 1960s something of a given. That lauded tribe of European rule-breakers took what they needed from cinema history and broke the rest, changing the way that people thought about and interacted with film in a manner that’s irreconcilable with your standard biographical entry. Jean-Luc Godard, the subject of Linklater’s latest, Nouvelle Vague, would surely scoff at the notion of stuffing his work and influence into such a rigid box, but at least it’s coming from someone with an outsider’s touch. We found the right helmer to twist the architecture enough to match Godard’s rascally ways, if only those parameters would show a little leniency.

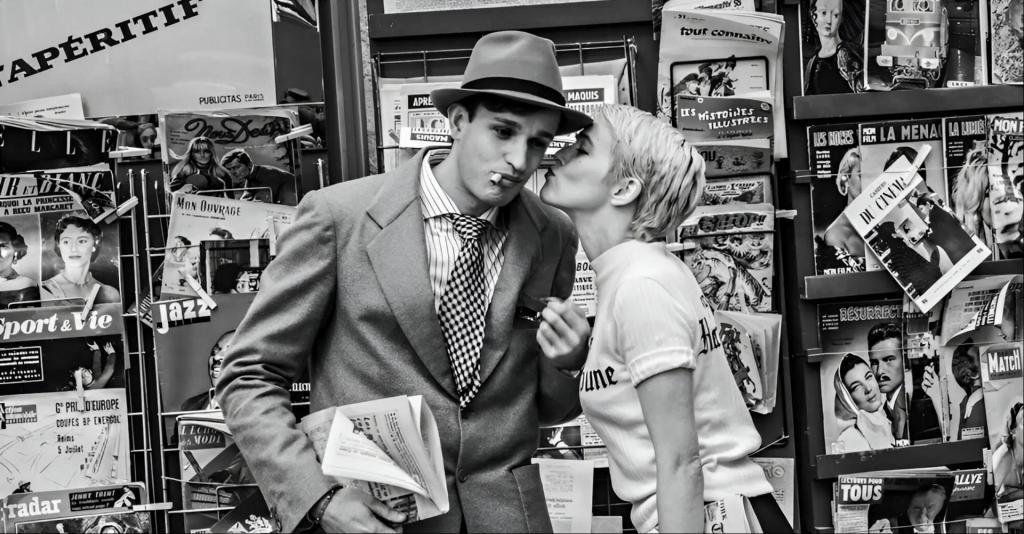

The Godard (Guillaume Marbeck) we meet in the opening passages here has got plenty of the stuff to go around, even if he tends to hoard it for himself. A critic for the now-hallowed film publication Cahiers du Cinéma, the young upstart is itching to train his attention on the other side of the lens, looking to follow in the footsteps of his wunderkind peer François Truffaut (Adrien Rouyard). The much-ballyhooed release of his colleague’s debut feature, The 400 Blows, has opened the monetary floodgates for their entire collective, and Godard isn’t about to let it shut before sneaking in, mounting his debut feature with precious little preparation beyond a basic plotting framework. After easily persuading Jean-Paul Belmondo (Aubry Dullin), an actor he’d previously worked with on a short film, to sign on to the project, Godard goes star hunting, landing Jean Seberg (Zoey Deutch) for the co-starring role, though it’s far from a perfect match. Her adherence to the do’s and do not’s of the industry clashes mightily with Godard’s devil-may-care attitude, creating a friction that helped inspire the director’s all-time world cinema classic, Breathless.

That’s right, he wins at the end, setting up the exact same paradox that always presents itself when niche figures are up for portraiture; if you know, you know, and if you don’t, that’s probably not an accident. Godard and Truffaut are figures of reverence within a certain community, and any chance to pal around with them in their heyday is catnip to your neighborhood cinephile, but their legend has already been told across innumerable books and documentaries, not to mention their own filmographies. Your annoying friend with the Andrei Tarkovsky coffee table book already knows everything that Holly Gent and Vincent Palmo’s screenplay has to tell them, while the uninitiated will be drowning in a sea of information, desperately grabbing for some landlocked point of reference. At least that’ll keep their heart rate up, because Nouvelle Vague is firmly in cruise control.

Linklater is no stranger to a low-humming frequency, having made his name on beloved hang-out flicks like Dazed and Confused and the Before trilogy, but his controlled temperature setting works better sometimes than others. Though not as relentlessly monotonous as his 2022 rotoscope snoozerApollo 10 1/2: A Space Age Childhood, the auteur’s penchant for letting the chips fall as they may gets the better of him here, resulting in a movie that’s as aimless as Breathless’ fabled production. The mirroring is obviously intentional, but engagement isn’t predicated on simply doing your homework, and Nouvelle Vague’s languid, meandering structure has a way of weighing down eyelids. Katia Wyszkop’s ravishing production design, when paired with cinematographer David Chambille’s enveloping grainy, black-and-white camera work, make for quite the lived-in, era-appropriate world, but all that comeliness is a double edged sword. When the bath you’ve drawn is this warm and inviting, you can’t really blame the bather for nodding off in the tub.

Cue the actors, who, beyond embodying their non-fiction avatars, are here to grab you by the shoulders for a light tossling, though everyone here seems beholden to Linklater’s glassy waters. Dullin barely makes a ripple, allowing his easy-going charm to be subsumed by the movie’s gentle white noise. Deutch doesn’t go out so quietly, her constant bristling over Godard’s laughably truncated shooting schedule and general laissez-faire approach providing the film with some desperately-needed traction, not that Jean-Luc could be bothered to notice. Enervating, pretentious, and condescending, Marbeck plays Godard as such an egomaniac that you start to wonder about Linklater’s baseline affinity for the movie’s centrifugal force, an inkling bolstered by the filmmaker’s open admission to being more of a Truffaut guy in the first place. His affections are trained on the time and place writ large, reveling in small, elucidating moments like when Roberto Rossellini receives a king’s welcome from the Cahiers du Cinéma staff, only to shove a handful of finger sandwiches to his bag before exiting the building. The French New Wave might have mythical status today, but in the moment, they were all just trying to get by.

Aligning these artists’ workaday realities with their ongoing importance is a near-impossible task, and for the most part, Linklater simply focuses on the latter tenet, packing his movie with enough blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameos to turn the whole thing into the nerdiest Marvel flick ever. His heart’s in the right place, and while most biopics are regarded with a well-earned level of skepticism, Nouvelle Vague’s passion for its players and environment is evident in every frame. It’s just juiceless, too enthralled with its own game of dress-up to reach out toward its audience, a strangely sterile compendium for Breathless, which is determined to hold your attention by any means necessary. There are worse things to be than amiable, and while Netflix scans as an odd place for something with such a vanishingly small target audience to exist, Nouvelle Vague might be best suited for the streamer’s passive, at-home viewing experience. It’s more wallpaper than movie anyway, comforting fuzz as you drift off to sleep.

Leave a comment