The American people, fed up with all the liberal propaganda and a purported rise in criminal activity, have decided to turn back the clock. A tall, white savior, familiar to the masses from his years on television, throws his hat in the political ring, promising a return to Christian values, a crackdown on crime, and a tax cut-assisted boost to the economy. After vanquishing his charm-bereft opponent by a sturdy margin, the new commander-in-chief achieves hero status in conservative pockets of the country, while appalling left-leaning individuals with both policies and rhetoric. Where some see a return to sanity, others perceive an off-ramp to dystopia, with widespread deregulation allowing corporations to swindle and poison their consumers, and empathy only afforded to those in accordance with the law. It should be obvious by now, but in case you’ve been living under a boulder, let’s give the man a name: Ronald Reagan.

What, were you expecting someone else? The constant churn of unbelievable headlines and dire discussion topics has a way of making us all prisoners of the moment, but Donald Trump’s presidency isn’t exactly unprecedented; In fact, it’s hard to think of two oval office occupants who compare quite so readily as Reagan and Trump. Surrounding factors have changed much more than ideologies, with media consumption and stratification among our biggest breaks from the past. As the distribution of information has sped up, the production of (and engagement with) movies has slowed down, with film studios largely abandoning modestly-budgeted features with quick production turn-arounds for multimillion dollar affairs that take years to get off the ground. It’s No Country for Old Men filmmakers looking to offer contemporaneous commentary, but the delivery system wasn’t always so laborious. Those looking for a movie to help laugh through the pain or revel in the pleasure of our present moment won’t find any balm at the local multiplex, but there’s ample supply in the form of Reagan Era Satire.

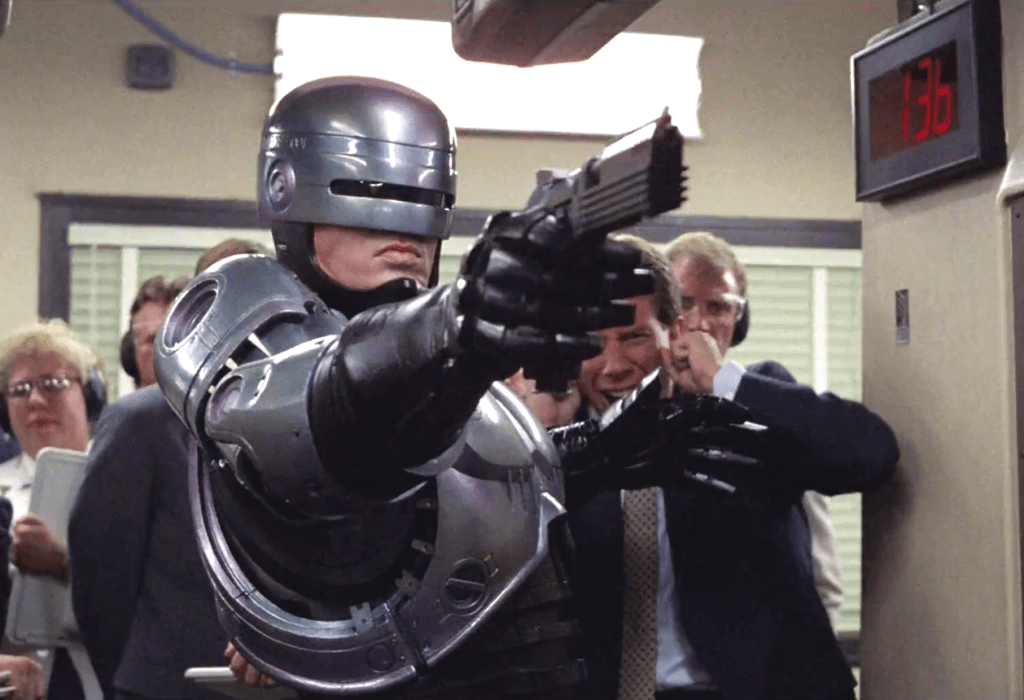

With reports of cities in disarray and delinquents running amok, Americans looked to the star of Bedtime for Bonzo, and the citizens of Detroit put their faith in RoboCop. Premiering at the tail end of the Reagan administration, Dutch filmmaker Paul Verhoeven’s first foray into stateside cinema wears all the markers of its gaudy, militarized moment, but the best caricatures always harbor an affinity for their subject. As streamlined as it is silly, the movie sees policing tough guy Alex Murphy (Peter Weller) fall victim to a hail of gunfire in the early goings, allowing shady weapons manufacturers Omni Consumer Products (OCP) to use his bullet-riddled body as a guinea pig. Soon, our titular hero is off and running… or rather stalking around at a cumbersome pace, with Weller’s enormous, unwieldy suit perfectly visualizing the preference for shock and awe over utility and exactitude. Goofy as his metallic armor may be, the sheer bombast makes sense as a metaphorical safety blanket for some, and a leering optical threat to others. When delivering a simple message to the youth of Michigan’s largest metropolis, our eponymous tinman’s foreboding suggestion (“Stay out of trouble”) says the loud part loudly; The clean-up man is on his way, and he doesn’t do nuance.

This gunslinger approach doubles as a mission statement for screenwriters Edward Neumeier and Michael Miner, who use their futuristic setting to survey the national zeitgeist from myriad angles. Opening with a news broadcast that nonchalantly relays stories of impending nuclear holocaust and street-level carnage, RoboCop doesn’t suggest that the general population has become numb to all the melee so much as enraptured by it, with celebrity miscreants and their eventual punishment serving as steady, monocultural entertainment. It certainly doesn’t hold the space all on its lonesome, with the movie’s constant cutaways to fictional advertisements and bawdy sitcoms forging a world of omnipresent distraction and aggressive commercialism. By the time one of the flick’s anonymous villains meets his demise after crashing into a barrel of toxic waste, there’s no question as to who is really being overtaken by waves of hazardous sludge.

Wading through all that drek and misinformation would certainly be easier if there was a way to cut through the clutter, a scenario that met the silver screen just one year later in They Live. Like the previous film’s garish costume, writer/director John Carpenter’s 1988 cult classic uses the era’s gouache idea of fashion against itself, swapping out the oversized artillery for a simple pair of bulky sunglasses. More gift than curse, they allow their wearers to see through billboards and magazine covers to reveal oppressive undercurrents, the subliminal messaging exposing a clandestine alien invasion. Newly radicalized by the uncovered truth, the movie’s unnamed protagonist, feebly played by professional wrestler “Rowdy” Roddy Piper, immediately takes action, lethally assaulting the disguised extra terrestrials in front of bystanders who remain oblivious to the cover-up. You could hardly blame them for their shrieks of terror, though the audience has already been primed for a mismatched fight by a previous depiction of barbarity against the unarmed.

It takes place during the flick’s languid opening passage, wherein Piper ambles into town like a post-prime Russell Crowe doing his best Clint Eastwood impersonation. After taking up work and residence in a Los Angeles shantytown, the protagonist’s unenviable digs are beset by local law enforcement, destroying the nascent community at the behest of their celestial overlords. Plot wise, the destruction is spurred by a search for the freedom fighters responsible for inventing the aforementioned shades, but Carpenter’s empathy for the beleaguered common man was inspired by contempt for a real-world antagonist. Released mere days before the 1988 presidential election, They Live positions Reagan himself as a galactic insurgent, seen speechifying on a nearby television in the same ghoulish make-up worn by every actor charged with playing an inter-planetary malefactor. As a political statement by way of B-movie, George H. W. Bush’s landslide victory proved the movie’s lack of true life efficacy, but the voters unwittingly proved his point. With this many diversions in the air, politicians can do as they please under cover of largess.

Obstruction came to be Carpenter’s primary concern near the end of Reagan’s second term, but at the top of his first, mass incarceration appeared much more wearying. Despite being conceived and written in response to the Watergate scandal, Escape from New York’s police state anxiety couldn’t have arrived at a more pertinent time than 1981, the start of an eight year period that saw the United States’ imprisoned population nearly double in size. Projecting forward in that exact window of time must have greased the creative wheels, as the opening title cards pinpoint 1988 as the year in which Manhattan Island was repurposed as a maximum security penitentiary, housing an untold number of culprits with no intention of later release. Less than a decade later, the Big Apple centerpiece has transformed into an admonitory hellhole, one that Snake Pliskin (Kurt Russell) is dropped into on a search-and-rescue operation that doubles as a suicide mission, seeking to find and extricate the sitting president, whose plane has just crashed within the borough’s barbed-wired parameters.

Engine failure isn’t the cause of the plummet, but rather a carefully executed terrorist attack that cites ecological degradation and systemic racism among its motivating factors, alluding to an unseen nation of distressed civilians. Being persecuted by your own elected officials will do that, and while the movie’s luxuriously grim sets and Carpenter’s all-timer score signal titillation and adventure, Escape is more attuned to dreary allegory than lacerating comedy. Forcing thousands of ne’erdowells to fend for themselves under an eternally darkened skyline is dehumanizing in a manner that offers little room for misinterpretation, even if Carpenter confounds his message by dressing many of them in the type of countercultural attire that scared many voters into siding with Reagan. It’s a misjudgement that likens black and queer signifiers to amorality, though the shadowy figures that guard the gates are always higher up on the film’s pecking order of scorn.

Allowing an untold percentage of the national census to suffer just out of sight prompts sympathy for their plight, though The Running Man redirects our derision by moving them front and center. Director Paul Michael Glaser’s sophomoric sophomore theatrical feature takes its cues from Stephen King’s 1982 novel of the same name, unfurling at the imagined conclusion of the 2010’s, wherein a revised iteration of ancient Rome’s gladiator games has become the most popular program on television. Rather than responding to a casting call, the contestants are handpicked by unscrupulous host Damon Killian (Richard Dawson), who peruses detention center listings to find appealingly vile combatants for his lethal, highly rated game show. One look at Ben Richards (Arnold Schwarzenegger), an officer wrongly accused of opening fire on a band of defenseless protesters, is enough to whet Killian’s debased appetite, though it wouldn’t be an Arnold flick if some payback wasn’t in the offing.

Or if bad acting wasn’t a feature masquerading as a bug, with Schwarzenegger dutifully delivering one catch phrase clunker after another while completely failing to bring anything resembling pathos to the role. Flawed by design rather than execution, the former weightlifting champion is in good company where poor performances are concerned, the flick stuffing itself to the gills with stunt casting that’s aged like yogurt since its 1987 release. The struggles of Jesse Ventura, Jim Brown, and Mick Fleetwood, while enjoyable if viewed derisively, make genuine buy-in all but impossible, and are worsened by both Glaser’s incompetent direction, and set designs that would later be found at your local laser tag arena. Only Dawson manages to make it out unscathed, playing into the untrustworthy undergirding of his Family Feud persona to locate something delectably malicious. It’s surprisingly convincing for an untrained actor, but there’s something fitting about an icon of the small screen slotting so seamlessly into a dystopia wherein his real-life day job has ensorcelled the public.

Of all the motifs that are shared across these four films, a brain cell-frying obsession with TV is easily the most prominent. Only Escape declines to present the glowing household box as a sedative for the proletariat, though ignoring its enveloping pull has more to do with timing than anything. Carpenter’s first anti-establishment offering came on the heels of an election rather than in the wake of its result, six years before the 16-month span in which the other three features were deployed. He more than makes up for lost time with They Live, wherein the signal that allows our martian captors to maintain their disguise is beamed directly from a southern California studio. If that seems cloyingly literal, it’s worth observing the hair-trigger anger that several characters show early on when a hacker interrupts their regularly scheduled programming to warn of the oncoming apocalypse. When pixelated complacency is this addictive, no one thinks to look under the hood of its source.

Speaking of interruptions, RoboCop peppers its narrative with faux-news bulletins and jaunty advertisements, culminating in the promotion of a Risk-style board game entitled Nukem, which does exactly what it says on the tin. While ostensibly breaking from the yarn at hand, these intervals say more about the erosion of attention spans than clumsy dialogue ever could by means of relentless diversion. They’re spliced into The Running Man in a much less abrasive fashion, but the commercial for Climbing for Dollars, another gameshow with a moribund hook and literally elevated stakes, is in keeping with Verhoeven’s desensitized, consumerist mockery. Reaching the top of the rope may yield a huge financial windfall, but the victors of the movie’s titular contest, shown enjoying their winnings amidst conspicuously fraudulent tropical settings, seem wholly satisfied with their non-monetary consolations.

Who needs piles of cash when the same arms that reach around them could be holding beautiful women, one on each side? This allusion to philandering bliss, which is similarly depicted in the nameless sitcom that dominates the airwaves throughout RoboCop, needles in much the same way as the two movies’ ironic adverts, but Verhoeven and Glaser misstep in their equating of the fairer sex to disposable product. You never doubt the intention, but in a pseudo-genre that seems resolved against female intervention, the chiding defeats its own sneering purpose. Women are only hangers-on here, clutching the well-muscled arms of these films’ heroes, watching Reaganism’s downfall with the same fleeting agency as the lobotomized masses that all three filmmakers are so desperate to lampoon. At least Snake Pliskin doesn’t have to fend off any of Running Man’s disreputable suitors; the sprawling cast of Escape from New York only finds space for two feminine representatives, and there’s less than one fully realized person between them.

Dimensionality is far from a guarantee in this environment, and the shared scoffing at dehumanization has a way of bleeding into its promotion. These are action flicks, after all, and cannons need fodder, requiring gaggles of anonymous targets to meet grisly ends without pulling audience sympathy away from our heroes. The point is a salient one, reckoning with the thick, black line that conservative discourse often lays down between the good folks and the bad, but cosplaying thoughtless discrimination has a way of morphing into the real thing. Politicians have surely failed Escape’s inmates, just as mass media had callously demonized The Running Man’s combatants, but neither Glaser nor Carpenter are interested in coloring in the hopeless hordes on an individual level, lest the open wounds become too traumatizing. This use of the enemy’s tools extends to all the bloodshed, at once winkingly intentional and slightly self-defeating. That old canard about how you can’t make a war film without valorizing combat applies just as readily here; it’s hard to take the machine down from the inside when you’re busy pulling all of its levers.

Only so much reinvention is possible when you’re modeling your movie after the foundational genre of American filmmaking, as all four flicks do with the Western. The mano y mano shoot-outs and abandoned city streets have been swapped out for automatics and skyscrapers, but there’s no mistaking any of these tight-lipped out-of-towners for anything other than the new sheriff on the cite. Scores aren’t often settled with words when Tinseltown goes tumbleweed, and regressing to the violence-fighting-violence standard of early cinema feels like following suit in a society that’s doing the same. There are plenty of clips to be emptied in the tussles, but the most memorable brawl across the quartet is They Live’s bareknuckle beatdown between Piper and Keith David, a delirious grunt fest that goes on long enough to charge through gratuity into glory. Thank god the cops never show up; lord knows they’ve got their hands full elsewhere.

For all the larger military concerns littered across Carpenter, Verhoeven, and Glaser’s films, each directs their attention to neighborhood forces rather than proper battalions. They’re largely groundskeepers in both Running Man and Escape, quietly ensuring that contestants and inmates don’t step outside of carefully mandated order, but They Live and RoboCop aren’t satisfied with that kind of sidelining. The former takes them to the gun range, with a sizable portion of the alien invaders dawning the badge, their human counterparts largely falling in line with the new world order. It’s a scathing and adversarial take on law enforcement, one that Verhoeven, for all his enviable stores of vitriol, can’t quite match. RoboCop might not champion the boys in blue the way that 80’s ticket buyers expected, but it does take pity, frequently attesting to their thoughtless deployment by unfeeling powerbrokers. Even the invention of Robo himself speaks to Neumeier and Miner’s shared sympathy, condescending as it may be. These guys need help if they’re going to get anything right, and nothing could be more effective than a police officer without all those inherent human failings.

Which some, including all the directors here, would call liberties, though the distinction would be coming out the side of their mouths. Language is a powerful thing, especially when geared empty galvanization, and written reminders of precious freedom and sweet, sweet justice are littered throughout the sets and background details in all three films. One gets the feeling that everyone involved was feeling a little inundated with demands for obedience trojan horsing as fatherly pleas for unity, a cloak and dagger operation that’s never had the same sway on larger cities. New York, Los Angeles, and Detroit are some awfully big names to end up hosting these movies on accident; the next time you hear a right-leaning politician defame the population of an entire metropolitan area, try to keep in mind just where, exactly, the ideological leanings tend to tilt when folks live with one another en mass.

It’s usually not with bloated systems of power, which is what makes Hollywood’s general liberalism sort of paradoxical. One of America’s largest and most costly industries, movies’ reflexive distaste for conservatism can’t help but lack self-awareness, leading to some of the well-intentioned fumbles listed above. Leave it to an outsider like Verhoeven to land the funniest and most predictive joke in any of these features at the end of RoboCop, when the eponymous avenger finally vanquishes his last foe, and is asked for his name in victory’s aftermath. “Murphy,” he replies, despite no longer residing in the flesh and bone that once bore the moniker, cursed to wear his work uniform until his dying, mechanical breath. He’s a good man, that Murph; the first, and hopefully last, example of blue lives literally mattering.

Leave a comment